The year was 1989! It was my freshman year at the campus on the highest of seven (7) hills; Florida A&M University, located in Tallahassee, Florida. A virgin to college life from Miami, Florida, I walked the facility’s grounds on a daily basis taking in the essence of being in an environment with my peers from all corners of the United States, away from home for an extended period for the first time. The variations of complexions, the array hues, the beautiful women, the sternness of the men, the overall history surrounding my every being was overwhelming. I can remember a young man approaching me, no older than 19, leather jacket (this was in the summer, late August mind you), afro with his pick deeply entrenched in the back pocket of his blue jeans, handing me a flyer, looking me squarely in my eyes behind the lenses of his sunglasses and asking me if I were ready for the “Revolution?” “Hell yeah”, I responded. (What?) Man… what da hell am I talking about? I’ve just arrived on “da yard” and I better not sh*t on my parents money or this little scholarship I have trying to be radical. That would soon come though. As the days passed, I noticed people wearing college apparel with a patch that read, “40 Acres and a Mule”. The clothing was fashionable and I wanted to learn more about it since I was unfamiliar with the brand and the slogan. I would come to learn to that the merchandise was owned by an aspiring director by the name of Spike Lee and the concept was based on a famous episode during the Civil War/Reconstruction era where in 1865, Union General William T. Sherman issued “Special Field Order 15”, which ordered distribution of lots of forty (40) acres to freed black families and could be lent some surplus army mules. This was the first systematic attempt to provide a form of reparations to newly freed slaves by redistributing property formerly possessed by Confederate land owners.

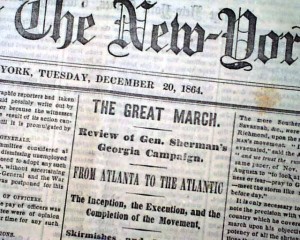

As the story goes and what has been taught in school, the policy of “40 Acres and a Mule” was that General Sherman issued the Order on January 16, 1865, after his famous “March to the Sea” where his military campaign began in the captured city of Atlanta, Georgia on November 15, 1864 and ended with the capture of the port of Savannah, Georgia on December 21st of that same year. However, what isn’t told is how the idea of the Order was generated by black leaders. A discussion was had between Sherman, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and twenty (20) leaders of the Black community in the City of Savannah, where Sherman was headquartered four (4) days before the Order was issued. Abolitionists Charles Sumner and Thaddeus Stevens and other Radical Republicans had been actively advocating land redistribution “to break the back of Southern slaveholders’ power.” The Radical Republicans were a faction of American politicians within the Republican Party from about 1854 until the end of Reconstruction in 1877. They called themselves “radicals” and were opposed during the war by moderates and conservative factions led by Abraham Lincoln and after the war by self-styled “conservatives” and “liberals”. Radicals strongly opposed slavery during the war and after the war distrusted ex-Confederates, demanding harsh policies for the former rebels, and emphasizing civil rights and voting rights for freedmen. The meeting was held at 8:00 p.m., Jan. 12th, on the second floor of Charles Green’s mansion on Savannah’s Macon Street. The Black leaders were all ministers, mostly Baptist and Methodist; eleven (11) of which had been born free in slave states, of which ten (10) had lived as free men in the Confederacy during the course of the Civil War. The question was raised by both Sherman and Stanton as to what did the Negro most wanted? Land! “The way we can best take care of ourselves,” Rev. Garrison Frazier began his answer to the crucial third question, “is to have land, and turn it and till it by our own labor … and we can soon maintain ourselves and have something to spare … We want to be placed on land until we are able to buy it and make it our own.” And when asked next where the freed slaves “would rather live — whether scattered among the whites or in colonies by themselves,” without missing a beat, Brother Frazier (as the transcript calls him) replied that “I would prefer to live by ourselves, for there is a prejudice against us in the South that will take years to get over … ” Rev. Frazier was the group’s chosen leader, a Baptist minister, who at the time was sixty-seven (67) years of age, who had been born in Granville, North Carolina, and was a slave until 1857, “when he purchased freedom for himself and wife for $1000 in gold and silver,” as the New York Daily Tribune reported. Rev. Frazier had been “in the ministry for thirty-five years,” and it was he who bore the responsibility of answering the 12 questions that Sherman and Stanton put to the group.

Upon the Order being issued, the response was immediate. When the transcript of the meeting was reprinted in the Black publication Christian Recorder, an editorial note indicated that “From this it will be seen that the colored people down South are not so dumb as many suppose them to be.” Baptist minister Ulysses L. Houston, one in the group of men that had met with Sherman, led 1,000 Blacks to Skidaway Island, Ga., where they established a self-governing community with Houston as the “Black governor.” By June of that year, “40,000 freedmen had been settled on 400,000 acres of ‘Sherman Land.'” Sherman later ordered that the army could lend the new settlers mules; hence the phrase, “40 acres and a mule.” Below are excerpts of the Order:

Section one: “The islands from Charleston, south, the abandoned rice fields along the rivers for thirty miles back from the sea, and the country bordering the St. Johns river, Florida, are reserved and set apart for the settlement of the negroes [sic] now made free by the acts of war and the proclamation of the President of the United States.”

Section two specifies that these new communities, moreover, would be governed entirely by black people themselves: ” … on the islands, and in the settlements hereafter to be established, no white person whatever, unless military officers and soldiers detailed for duty, will be permitted to reside; and the sole and exclusive management of affairs will be left to the freed people themselves … By the laws of war, and orders of the President of the United States, the negro [sic] is free and must be dealt with as such.”

Finally, section three specifies the allocation of land: ” … each family shall have a plot of not more than (40) acres of tillable ground, and when it borders on some water channel, with not more than 800 feet water front, in the possession of which land the military authorities will afford them protection, until such time as they can protect themselves, or until Congress shall regulate their title.”

With this Order, 400,000 acres of land — “a strip of coastline stretching from Charleston, South Carolina, to the St. John’s River in Florida, including Georgia’s Sea Islands and the mainland thirty miles in from the coast,”

So you then ask yourself, if all of this transpired, what happened to cause people of color to continue to feel disenfranchised and left in a state of suffering and misery? After Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s successor and a sympathizer with the South, overturned the Order in the fall of 1865, and, as Barton Myers remarked, “returned the land along the South Carolina, Georgia and Florida coasts to the planters who had originally owned it” — to the very people who had declared war on the United States of America.

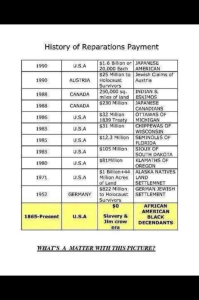

Most startling is that reparations were paid to former slave owners during the Civil War. The District of Columbia Emancipation Act began just after President Lincoln signed the bill to end slavery in the district on April 16, 1862, and during the next nine (9) months, 930 former slave owners were compensated by the Board of Commissioners. According to the National Archives and Records Administration, the former slave owners were given up to $300.00 emancipation compensation for each slave they owned, after being forced to give their captives freedom. This amount was given to cover any loss they may incur for not having their slaves to work their land and make money for them. They were also compensated for their loyalty to the Union throughout the duration of the conflict. Ain’t that some sh*t!

So in reading all of this information, and grasping all of this history, you ask yourself why now? Why am I being inundated with all this talk of reparations? On May 21, 2014, Ta-Nehisi Coates, writer for a publication called The Atlantic, published an article called “The Case for Reparations – Two hundred fifty years of slavery. Ninety years of Jim Crow. Sixty years of separate but equal. Thirty-five years of racist housing policy. Until we reckon with our compounding moral debts, America will never be whole.” And in this compelling article, it focused on the atrocities which have befallen people of color since their arrival on the shores of the Atlantic those hundreds of years ago; how housing discrimination, the inability secure loans, areas in which people are forced to live, all play a role in the current plight of the so-called African-American. Since then, the subject has been broached on our show and Melissa Harris-Perry’s show on MSNBC. So why now, because advocates such as Representative John Conyers (Democrat – Michigan) have suggested the creation of a Commission to Study Reparation Proposals for the African-Americans, H.R. 40. It doesn’t matter that African countries also sold their own kind into slavery; the descendants responsible and those who were victims have long since passed. Those wrongs of yesterday continue to have adverse effects on the present and will have long-standing consequences well into the future. It’s amazing how a piece of clothing and an individual’s dream to shed light on the “Black” experience can jog the consciousness and spark a “revolution.” “We Are The Change!” I’m gone! (b)

Note: Information was gathered from Henry Louis Gates, Jr.’s article “The Truth Behind 40 Acres and a Mule”.

Follow the Fan Page on Facebook : The Porch Reloaded – Rocking Chair Rebels

Follow us on twitter: @ThePorchFellas

Email us: theporchfellas@yahoo.com

Listen to the show on Thursday nights at 7:00 pm: www.theporchfellas.com on the Anti Robot Network